Unbuilt Emory

Architect Henry Hornbostel's campus plan evoked visions of Babylon,

but when the bills came due, Bishop Candler balked. Architect Henry Hornbostel's campus plan evoked visions of Babylon,

but when the bills came due, Bishop Candler balked.

By Andrew W.M. Beierle

Emory Magazine, March 1987.

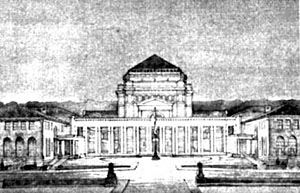

To stumble across architect Henry Hornbostel's original plans for the new

Emory campus in Atlanta is to experience much the same thrill an archaeologist must feel

unearthing a lost city. Hornbostel's vision has an almost Babylonian lushness to it--a

touch of Xanadu in Druid Hills--and it is made all the more alluring by the knowledge that

it was never brought to fruition. In the original plans a mammoth central building topped

with a pyramid of terra-cotta tiles dominates the Quadrangle. The Theology Building and

the Old Law Building flank the stately giant, joined to it by an elegant colonnade; two

obelisks mark the entrance to the courtyard created by the juxtaposition of the three

buildings. Executed in golden hues (with lavender shrubbery), the rendering suggests an

opulent academic oasis risen shimmering out of the red Georgia clay.

Alas, Warren Candler was not impressed. The parsimonious Methodist bishop, who

then served as both chancellor of the University and a member of the building committee,

would have none of the Beaux-Arts grandeur the Pittsburgh architect had dreamed up.

Candler was not pleased that construction costs of two of the first four buildings on the

Atlanta campus were already far above the prices agreed upon. The Law Building's final

price tag was 37 percent higher than the original estimate of $75,000, and the Theology

Building, budgeted at $100,000, had cost nearly $140,000. Candler was determined to put an

end to the spiraling costs, and he fired off a letter to Hornbostel on January 24, 1917. Alas, Warren Candler was not impressed. The parsimonious Methodist bishop, who

then served as both chancellor of the University and a member of the building committee,

would have none of the Beaux-Arts grandeur the Pittsburgh architect had dreamed up.

Candler was not pleased that construction costs of two of the first four buildings on the

Atlanta campus were already far above the prices agreed upon. The Law Building's final

price tag was 37 percent higher than the original estimate of $75,000, and the Theology

Building, budgeted at $100,000, had cost nearly $140,000. Candler was determined to put an

end to the spiraling costs, and he fired off a letter to Hornbostel on January 24, 1917.

As you will remember, from the start I have insisted that my policy was not to expend

large amounts in buildings; but to deliver the strength of our resources on the employment

of strong men. I regard strong men as more important to an institution than costly

buildings.

The buildings

already erected will constrain us to expenditures, despite all we can do, that were never

contemplated. I can not consider, therefore, at this time any further expenditures that

are likely to draw after them demands out of proportion to our resources. For example, a

costly colonnade will call for a still more costly central building, and that in tum will

call for buildings in keeping with it. If we move in that direction all my plans will be

more seriously deranged than they have been already by the expenditures which have been

made on the grounds and buildings. The buildings

already erected will constrain us to expenditures, despite all we can do, that were never

contemplated. I can not consider, therefore, at this time any further expenditures that

are likely to draw after them demands out of proportion to our resources. For example, a

costly colonnade will call for a still more costly central building, and that in tum will

call for buildings in keeping with it. If we move in that direction all my plans will be

more seriously deranged than they have been already by the expenditures which have been

made on the grounds and buildings.

Candler also complained to contractor Arthur Tufts, who supervised the construction.

Stung by the criticism, Tufts responded to the chancellor's letter on January 30.

I believe that if you knew of the untiring efforts of some of the men engaged in this

work, of their interest and zeal (wherein no interest ordinarily lies except that of

making a livelyhood [sic]) that you would be more pleased with the final results of their

work.

In justice to the architect, and to the men associated with me in this undertaking, I

feel that you should know that it is no small matter, within a period of fourteen months,

to convert a wilderness into the beginning of a great Institution, and I do feel that if

this work had been handled in the manner generally outlined by committees, that you and

the building committee would not only have been greatly annoyed, but the building plans

would have been delayed at least one year. . . .

Everyone concerned

knows that a great personal interest is taken in the development of the Institution by the

architect and by my associates in this office and by the man in charge of the actual

construction work. They have taken the ground, a wildwood as it were, and converted it

into a beautiful park. They have built road ways, paths, three permanent bridges, a

railroad siding, retaining walls, a sewerage system, water lines, an electrical system,

and the necessary mechanical apparatus for a permanent and lasting University, which

should, in the future, require no changes. They have erected four fireproof buildings that

we believe complete in every detail. They have studied the requirements for each

department that will occupy these buildings and they have put in these buildings the very

best material that could be had as demonstrated in the electrical apparatus, the heating

system, and all other material entering the construction of these buildings. Everyone concerned

knows that a great personal interest is taken in the development of the Institution by the

architect and by my associates in this office and by the man in charge of the actual

construction work. They have taken the ground, a wildwood as it were, and converted it

into a beautiful park. They have built road ways, paths, three permanent bridges, a

railroad siding, retaining walls, a sewerage system, water lines, an electrical system,

and the necessary mechanical apparatus for a permanent and lasting University, which

should, in the future, require no changes. They have erected four fireproof buildings that

we believe complete in every detail. They have studied the requirements for each

department that will occupy these buildings and they have put in these buildings the very

best material that could be had as demonstrated in the electrical apparatus, the heating

system, and all other material entering the construction of these buildings.

It is true that we could have used cheaper material which would have made the initial

cost less, but the future upkeep more. In the main buildings we have used the best steel

windows and plate glass, and all hardware in the buildings is of everlasting bronze. The

plastering in all the buildings is of the best material. The plumbing fixtures and piping

of the most lasting quality. The gutters and flashing of all buildings are of copper. In

fact, we have built for the future, more than for the present.

We have provided large basement rooms that we believe will be very valuable in years to

come. Some mistakes in planning and building we have doubtless made, but we do believe

that we have also done some good things and as a whole the sum of the good things more

than offset the mistakes.

Obstacles that have been overcome have been many, among them being the inaccessibility

of the work; you will recall that the [street]car line was not built until the work was

practically complete, necessitating both expense and delay in getting efficient labor. The

distance from the city also necessitates the maintenance of a camp and kitchen to take

care of the laborers. In the absence of water supply we established and maintained pumping

plants and tanks for construction purposes. We maintained surface toilets for sanitary

purposes, and in the absence of electrical power, we installed and maintained a complete

electrical plant in order to have lights and electrical power for construction. We found

it necessary to install an air compressor plant and pipelines to each building.

In July of last summer you will recall a long rainy spell, lasting for weeks and weeks,

which caused both delay and expense. You are also familiar with the great amount of mud

around the grounds, and the bad condition of the dirt roads around the University

property, all of which were unfortunate incidents and tended to expense and delay.

In your reference to the expenditure of money you perhaps have not considered the above

natural conditions nor the unprecedented conditions of the material market brought about

by the European War, which has caused prices of material to change over-night, and

deliveries to be delayed for months. The effects of which have been felt by all people

engaged in business.

I mention these things, believing your keen sense of justice will prompt you to

understand that the men intrusted Isicl with the physical development of Emory have been

faithful and sincere in their effort to produce everything which will be a lasting benefit

to generations to come, and which should be considered by you.

No contractor can make accurate estimate of cost until complete plans and

specifications are made. Under the circumstances it was impossible to accurately forecast

the expense of construction in detail, owing to the fact that the work had to be started

and finished with all possible speed, therefore, necessitating the actual commencement of

operations before the plans were finished. The plans for the . . . buildings now on campus

were finished only a short time before the buildings themselves were completed.

Inasmuch, therefore, as we have overcome almost all of the difficulties presented in

the labor situations and the handling of materials to and from by the improvements now

existing, the estimate for future development will be more accurate and you may rest

assured that every effort at my command will be used toward attaining this end, and that

the future construction will bear the high Standard which has already been established.

Hornbostel's response to Candler's pique came a week after Tufts', and he sounded many

of the same notes as the contractor. On February 6 he wrote the following letter to

Candler.

Your letter of [January] 24th I carefully looked over, and agree with you. I appreciate

your point of view and agree with you that it seems not possible at present to spend money

both for useful and beautiful buildings and on strong men to establish an important

university. Allow me, however, to make some observations. First, the buildings might be

too large, but they are not expensive. As an actual fact their cubage cost is less than

the educational buildings that have lately been erected for other colleges around Atlanta.

It is not fair to assume that, because the buildings are elegant looking and well built,

and commodious and appear as expensive structures, they run contrary to your ideas of

developing the educational standard of the University. It is true they have exceeded the

price established. This was not caused by the cubage price of the buildings, but by their

size, an element which was very hard to control, being insisted upon by the faculties.

Take for example the new Medical and Chemical Buildings; the requirements of the

faculties, even though Mr. Tufts and myself fought hard to reduce the demands for space,

forced us to make several plans for their buildings. The resulting structures, if

constructed and designed on present lines of university buildings, would far exceed their

appropriations. I wish to emphasize right here, with deserved vanity, that the ability of

Mr. Tufts and myself to produce commodious and large buildings, handsome in appearance and

of substantial construction, within and most likely lower than the price of similar

inferior looking buildings, is an accomplishment we are extremely proud of.

All the above

does not explain away the fact that more monies have been spent than contemplated, but

does tend to show that the monies expended have been expended most wisely. . . . If the

colonnade is ever built it will have to be a gift by somebody, and as a screen it would

probably allow us to build the central building less elaborate, because it would be a part

of it. My dear Bishop, I agree with you thoroughly in all you say, but somehow can not

help feeling that the energies expended so far on grounds and buildings have been wisely

applied, and in the right direction. The joys of nature and the environment of beautiful

things are an influence which is just as potent, and really more definitely certain in its

effect, than the direct and sometimes uncertain influence of strong individuals of an

efficient faculty. All the above

does not explain away the fact that more monies have been spent than contemplated, but

does tend to show that the monies expended have been expended most wisely. . . . If the

colonnade is ever built it will have to be a gift by somebody, and as a screen it would

probably allow us to build the central building less elaborate, because it would be a part

of it. My dear Bishop, I agree with you thoroughly in all you say, but somehow can not

help feeling that the energies expended so far on grounds and buildings have been wisely

applied, and in the right direction. The joys of nature and the environment of beautiful

things are an influence which is just as potent, and really more definitely certain in its

effect, than the direct and sometimes uncertain influence of strong individuals of an

efficient faculty.

I cannot but heartily compliment you and your people on the splendid beginning you have

made, and on the broad minded manner in which the affair was conceived and undertaken. The

grounds and buildings, I am sure, are a revelation to all those who visit them. My share

had given me enormous satisfaction, and I am happy for two reasons, one that the buildings

are successful, and secondly that I have had the opportunity to make your acquaintance,

and through you and your Mrs. to have been enlightened to appreciate the Southern people.

Looking north across Kilgo Circle toward the Quadrangle, this is how the central building

might have looked in the 1920s.

Tufts' and Hornbostel's eloquence notwithstanding, Warren Candler remained unsatisfied.

He was still uneasy about the considerable cost overruns, and his concem apparently led to

a falling out with his brother, Asa Griggs Candler, who had given the University $1

million to underwrite the move from Oxford to Atlanta. In fact, after a February 8, 1917,

meeting between Warren and Asa Candler and contractor Tufts, Warren wrote the following

letter, dated February 17, to Asa, offering his resignation as chancellor of the

University.

When the contract was made with Mr. Arthur Tufts for the erection of the buildings of

Emory University, I regarded it as an unwise and improvident contract; but out of

deference to your views and wishes I expressed no objection, trusting that the vigilance

of the building committee would make up for the lack of the usual service of an architect

employed by and responsible to the builder and would thereby protect the interests of the

University, notwithstanding the injudicious provisions of the contract.

In view of the fact that I was both the chancellor of the University and a member of

the building committee, I conceived that I had a double responsibility in the matter.

Accordingly, I have endeavored to meet that responsibility with pains-taking care and the

utmost fidelity.

I was, therefore, surprised and grieved when on last Thursday night, Feb. 8, in the

meeting with you and Mr. Tufts and Mr. Adams to which you had invited me, you rebuked me

in their presence for the manner in which I had endeavored to meet my responsibility.

It was so surprising and painful that I did not at the moment quite apprehend the

significance of the position in which I was unexpectedly placed nor the consequences which

must inevitably follow from the course you felt impelled to take with me.

Smarting naturally under the rebuke which you felt called upon to administer to me, and

feeling more keenly the humiliation by the administration of the rebuke in the presence of

Mr. Tufts and Mr. Adams, my first impulse, as you perceived perhaps, was to offer you my

resignation on the spot; but I restrained the impulse for more deliberate consideration.

After such consideration I am clear that I can not be of further service on the

building committee and that my efficiency as chancellor has been impaired and that I might

retire from the building committee at once and from the chancellorship at the next meeting

of the Board of Trustees.

I cannot contemplate for a moment the possibility of an estrangement from you, the

dearest of brothers, and I am convinced that it is my duty to take a course which will

make impossible the repetition of such a painful incident and that such a possibility

should be excluded by my retiring at once from any connection with the erection,

furnishing, or control of the buildings of the University.

My efficiency as chancellor of the University being impaired, and efficient service

being so necessary to this enterprise which is so important to both the church and the

country, I should not hold the position longer than the time required to go out quietly

and without sensation.

To myself, as well as to the University, I owe the duty of laying down responsibilities

which I can not discharge efficiently and to indicate the purpose to you, as President of

the Board of Tnustees, in time for you to seek a chancellor who can render the effective

service which the institution needs.

As chairman of the Educational Commission, and as one of the bishops of the church, I

shall stand ever ready, of course, to do anything I can to promote the interest and assure

the success of this all important enterprise which your munificent liberality has made

possible.

Candler did not, as it tums out, resign as chancellor over the matter of cost overruns.

Apparently he frequently sought to resign during the trying years of the founding of the

University: a check of University records indicates he threatened to do so as many as four

times for various reasons.

Hornbostel's plan for the Quadrangle--gracefully proportioned Italianate buildings

evenly spaced around a grassy central space--was essentially completed, but the

"costly central building" and the colonnade were never built. The architect's

romantic scheme remains today a wistful, unaccomplished dream. |